Medieval Waldensians: Calvinist or Arminian?

- 7 minutes read - 1394 wordsWhat did Waldensians believe about election and predestination? Were they Calvinist or Arminian? I could answer this question in a variety of ways, but I’ll try to keep it as brief as possible while still providing the key details derived from historical evidence.

Who Were the Waldensians?

The term Waldensian (also Waldense in English, Vaudois in French, Valdesi in Italian, et al.) first appeared around the 12th century, though some1 2 trace the movement back to as early as Pope Sylvester, the 4th-century Bishop of Rome under Emperor Constantine. In the Middle Ages, the Waldensians were a group of Christians who, to varying degrees, dissented from the Roman Catholic Church. In the early Modern era, their movement merged with the broader Protestant Reformation.

Predestination and the Waldensians: A Historical Overview

I’ll approach the question of predestination in reverse chronological order, beginning with the Waldensians in 2025, then following the trail back to the High Middle Ages.

Modern Waldensianism

Today, European Waldensianism is a relatively small Protestant denomination. Its center is in Torre Pellice, Piedmont, Italy, and it has about 170 congregations throughout Italy, particularly in Piedmont. The Chiesa Evangelica Valdese (Waldensian Evangelical Church) would be considered a mainline Protestant denomination if it were in the United States: its polity is liberal and progressive, as well as its theology. On paper, the Waldensian Evangelical Church holds a Calvinist view of predestination3, but like their mainline Protestant counterparts, this soteriology is not emphasized in their services. Thus, we can label modern Waldensianism Calvinist, but more out of tradition than adherence to a systematic theology.

The Calvinist Influence

The roots of this Calvinist tradition in the Waldensian movement can be traced back to the 16th and 17th centuries. The Waldensian Confession of Faith (1655) was accepted by a synod of Waldensian churches, and it closely with the Reformed tradition, particularly the French Calvinist (Huguenot) confessions of the time.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Waldensians became increasingly intertwined with the broader Reformed movement. The first French Bible translated from the original languages, Bible d’Olivétan (1535), was the work Pierre Robert Olivétan, a Waldensian minister and cousin of John Calvin. Olivétan was part of the Waldensian diaspora who had found refuge among the Swiss reformers in Neuchâtel. In fact, Theodore Beza (another key reformer, also known for his Greek New Testament) credits Olivétan with introducing Calvin to the question of the Reformation during their studies at the University of Paris4. Imagine that—a Waldensian was one of the catalysts of the monumental Institutes of the Christian Religion.

The strong connection between Waldensianism and French Calvinism began just before Olivétan published his translation of the Scriptures. In the 1520s, the small, preexisting dissenters known as Waldensians had come into contact with the Protestant Reformation. By this time, the Alpine valleys of Piedmont and the Dauphiné had been ravished by centuries of on-again, off-again persecutions, and their will to be separate had diminished. A segment of their itinerant ministers (generally referred to as barbes) wanted a line of communication opened with the Reformers and a potential reconciliation of their differing theological points.

1532 brought what is commonly called the Synod of Chanforan. Deep in the Angrogna Valley of northern Italy, many of the Waldensian barbes and laymen met with representatives of the Reformation, most notably, William Farel. Though little original material remains from these meetings, two major choices were made: the Waldensians would join the wider Protestant Reformation, and they would use their bibliological expertise to assist the Reformers by producing a French Bible translated from Greek and Hebrew instead of Latin (the aforementioned Bible d’Olivétan).

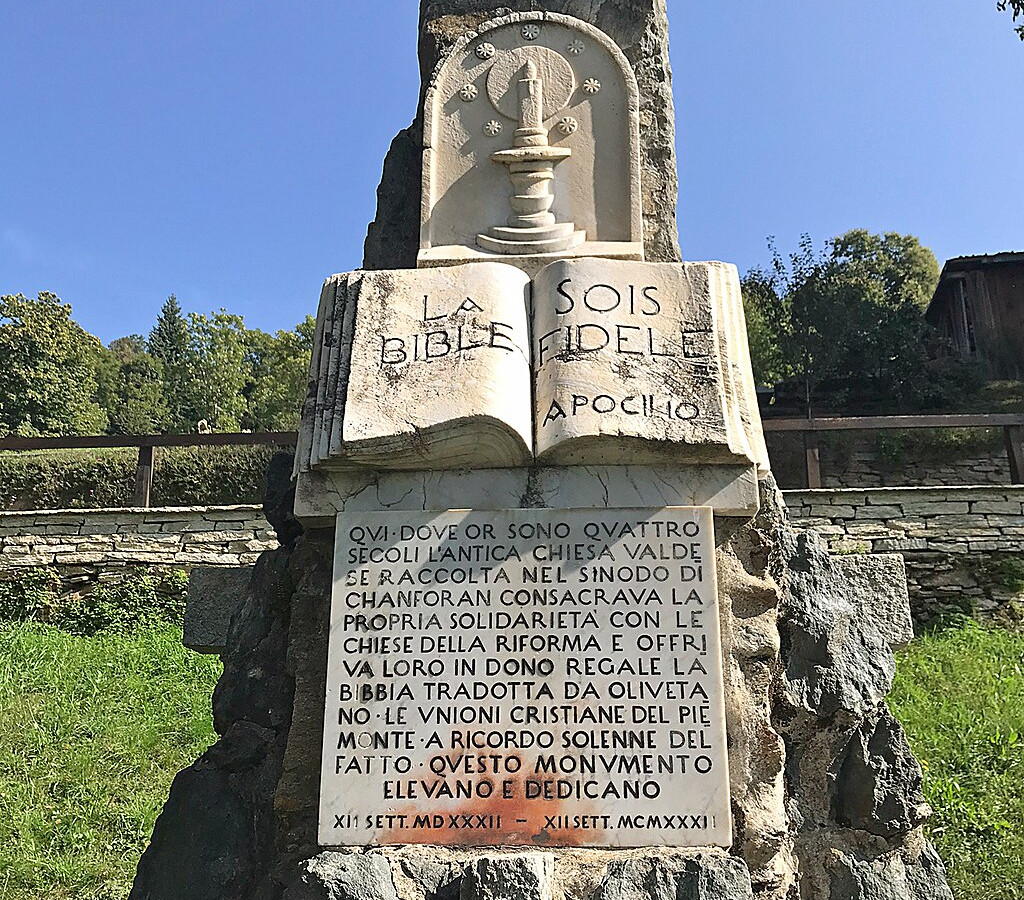

Monument to the Waldensian Synod of Chanforan in Valle Angrogna, Piedmont, Italy.

However, this meeting was not concluded without controversy. What was the main stumbling block for the Waldensians? According to Gabriel Audisio (a secular historian, I would add), it was the reformers’ doctrine of predestination. Audisio concludes that this subject threw the meeting into unrest: “some members demanded faithfulness to the past, and others turned their backs on former times to embrace new ideas that were set to ensure victory of the gospel.”5 This suggests that the Reformed doctrine of predestination, as articulated by Calvin and others, was an addition to the Waldensian tradition, rather than a doctrine already present among them.

I like how Audisio summarizes the Synod of Chanforan:

The Waldensian diaspora was swallowed up by the national Churches; former moral doctrines gave way to the new theology; the movement became a Church.… From this time on, where there had formerly been the spiritual descendants of Vaudès, there would stand Protestant churches.

How had this been possible? The Reformation had succeeded in doing what the Roman Church had not managed to do either by reason or by force. Persecution had failed to eliminate the Poor of Lyons but they were won over by persuasion. As a result, the old “Waldensian heresy” disappeared. The Poor of Lyons alone had survived into what are called modern times before being seduced—in every sense of the word—and enchanted by the Reformation. They turned to the Reformation, and vanished into its embrace.6

Medieval Waldensians

Looking back further, the itinerant barbes, who usually carried the Old Occitan translation of the Bible, visited groups of dissenters throughout southern and central Europe. Their theological positions were not as systematically developed as those of later Reformed or Arminian traditions. Regarding predestination, there is no clear statement in their writings. However, a passage from the Old Occitan poem, La nobla leyczon, contains a reference to the elect:

And give us to hear that which he shall say to his Elect without delay;

Come hither ye blessed of my Father,

Inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the beginning of the World,

Where you shall have Pleasure, Riches and Honour.

This passage is a likely allusion to Matthew 25:34 and doesn’t appear to be a formal doctrine of predestination. It’s more an expression of biblical faith than a systematic soteriological position. The medieval Waldensians did not develop a systematic theology, especially not one on predestination.

Were the Waldensians Proto-Arminians?

Waldensians did not articulate a formal doctrine on free will and prevenient grace, nor did they explicitly take sides in the later debate between monergism (God alone acting in salvation) and synergism (human cooperation with divine grace).

Could they be classified as Provisionists? Again, no—and it would be an anachronistic stretch to mold them into that view (though I would align myself with that system). The medieval Waldensians’ emphasis was on preaching, Scripture, and lay participation in religious life.

Diversity Among the Waldensians

I would also point out that medieval Waldensians were far from monolithic in their beliefs. Though many groups were labeled Waldensians (though they seldom called themselves that until the Reformation), some were doctrinally sound, and others held beliefs I would classify as unbiblical. Thus, what was written in 1350 about Waldensians in the Alpine valleys of Piedmont might be completely different from those in Bohemia in 1416. And those groups probably never knew each other existed.

The Waldensians in Historical Fiction

In my historical fiction series, Witnesses of the Light, I aim to portray the Waldensian view on predestination as accurately as possible by not emphasizing it. Medieval Waldensians did not focus on it, so why should the story? While Waldensians likely rejected extreme determinism, they also didn’t formulate a systematic theology of grace and free will like Arminius did.

In Heretics of Piedmont, The Lord of Luserna, and Prince of Savoy, I explore this topic only indirectly through a few chapter epigraphs I selected from figures on various sides of the issue: John Calvin, Theodore Beza, C. H. Spurgeon, John Wesley, Thieleman J. van Braght, and Lottie Moon (among others). However, none of the quotes I chose address predestination or election.

For us today, the Waldensian story is a reminder of the complex and often messy history of Christian faith and dissent.

-

La Nobla Leyczon, lines 410–415. ↩︎

-

Sir Samuel Morland, The History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piemont (London: Henry Hills, 1658), 8–14. ↩︎

-

Chiesa Valdese. Confessione di fede del 1655, 9–10, accessed February 6, 2025, https://chiesavaldese.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/01_cf.pdf. ↩︎

-

McKim, Donald K., and David F. Wright, eds. Encyclopedia of the Reformed Faith. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1992. ↩︎

-

Audisio, Gabriel. The Waldensian Dissent: Persecution and Survival, C.1170-c.1570. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1999, 167. ↩︎

-

Audisio, Waldensian Dissent, 167. ↩︎