Sifting through Waldensian History

- 12 minutes read - 2404 wordsI recently read a blog post by Pastor Tom Brennan titled, “How to Write a Book.” I’ve read two of his books and have been impressed by both the content and quality, so I knew his insight here would be valuable. A point he made in the post that caught my attention was this:

Only write a book if you have read at least twenty-five books on similar subjects.

I agreed, but then I wondered if I had read that amount for my two (almost three) fiction books. I realize nonfiction study is different from researching a novel, but still I think it’s a good standard to hold myself to. Had I done that though?

After I read the article, I counted the rows in my list of sources. Thankfully, it was over twenty-five (yes, I’m relieved), but then I started glancing at the titles and authors from a meta-perspective. Who was this author? What influenced him or her? Why did he or she write this book? Is it heavily biased without proof? Is it scholarly in tone, but lacking in faith? How much does it contradict other sources?

Waldensians (also rendered Waldenses in English, Valdesi in Italian, Vaudois in French) were a religious group that originated in the Middle Ages. There—I doubt anyone disagrees with that statement. From there the sources diverge widely; it was part of my duty to sift through it and distill the mounds of information for the very wide Christian Fiction audience.

Where I come from

Everyone has a bias. I understand some disagree with that statement, but I have yet to find an unbiased source on a historical subject. I’ve read criticisms of history curriculums like Abeka that declare them as Christian-slanted, and I doubt Abeka would disagree with that label. The inverse is true too: history published by secular publishers will have a secular bias—sometimes anti-Christian (especially in the 21st century).

I hold my own worldview and presuppositions. For example, I believe the Genesis creation account to be literal. That’s not based on feelings or instinct, but on my belief that the Bible is inspired, inerrant, and historical (all of those being presuppositions too, based on my faith). I love reading about scientific evidence of creation, but my beliefs are not founded on that. In areas where there appears to be a lack of evidence, I rely on the Bible and the faith it both demands and produces. My beliefs about the Bible itself are similar—God’s Word is both inspired and preserved, and where the historical accounts are scant, I still trust what the Bible says about itself first.

Humanist historians would scoff at that last paragraph, but they are not without their biases and presuppositions. One example of this is the progressive view of history—that belief which supposes humanity tends to better themselves over time. I’m not here to critique that view, but the reader can see how that would influence their view on history.

These biases can be both a blessing and a curse. The beneficial side of having a worldview gives me a foundation, without which study becomes aimless and fruitless. The harmful side, however, can lead me down a path of dishonesty and unreliability.

The key is discerning the truth, as is the case for all knowledge—not just history. And research is the method by which we obtain that knowledge.

Waldensian bibliographical categories

That brings me back to the Waldensians. I’ve written some about the research I’ve done (see here and here), but in the “Selected Bibliography” page in the back of my books, there are a variety of authors and sources, some of which hold a completely opposite worldview from me. That of course doesn’t make them worthless, but I’ve found that being able to categorize sources correctly has helped me sift through the various histories of the Waldensians. In the remainder of this article, I’ll outline these categories, including their merits, reliability, and accessibility. This list isn’t exhaustive, nor are the categorizations perfect, but I think they can help the curious understand the nuances.

Old Waldensians

Finding writings from the Waldensians themselves before the 1600’s is challenging. They exist, but there are few, and those that do exist are often doubted for their veracity.

La Nobla Leyczon (Mss.C.5.21., The Library of Trinity College Dublin)

La nobla leyczon (English: The Noble Lesson) is one of the most extant documents written by medieval Waldensians, and it offers a glimpse into the religious views of its writers. These are its opening lines:

O Brethren, give ear to a noble Lesson,

We ought always to watch and pray,

For we see this world nigh to a conclusion,

We ought to strive to do good works,

Seeing that the end of this world approacheth.

There are already a thousand and one hundred years fully accomplished

Since it was written thus, For we are in the last time.

We ought to covet little, for we are at the latter end.

We see daily the signs to be accomplished

In the increase of evil and the decrease of good.

These are the perils which the Scripture mentioneth

In the Gospels and Saint Paul’s writings.

No man living can know the end.

And therefore we ought the more to fear, for we are not certain

Whether we shall die to day or to morrow.

The whole tract is worth reading. It claims to have been written in the early 12th century (before Peter Waldo of Lyon and the supposed beginnings of Waldensianism), but most modern historians date it one hundred years after. I’ll explain a bit more about this in the following sections.

Like the 1st century apostles, it’s hard to imagine the Waldensians writing down beliefs that they didn’t hold within their souls. Declaring these beliefs meant persecution, and it’s partially why they can be a reliable source (though not perfect). Waldensians also wrote a tract about the antichrist (with plenty of allusions to the pope) and translated the New Testament into their vernacular (see here for more about that), in opposition to the religious and secular authorities of the time. Again, sources from the medieval Waldensians themselves are scant, but they are valuable and insightful.

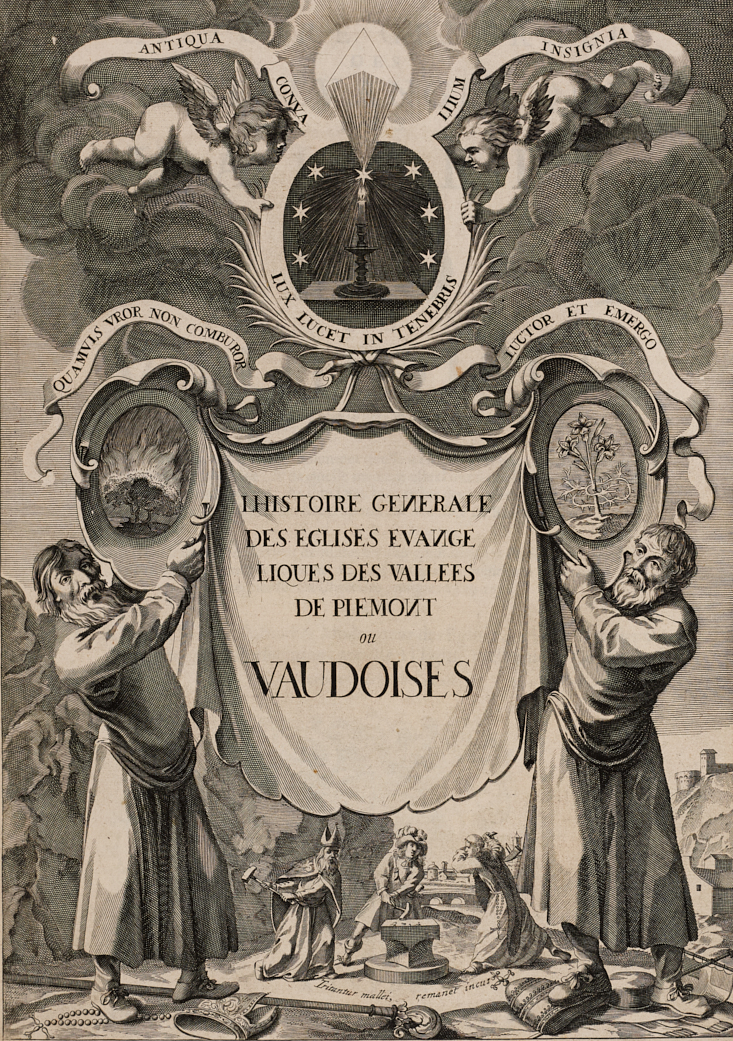

Fast-forward to the early 17th century. Waldensian writings become more extant, the most influential of which is arguably Jean-Paul Perrin’s History of the Ancient Christians Inhabiting the Valleys of the Alps; Jean Léger followed soon after with his General History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piedmont; Pierre Gilles was another Waldensian pastor and author in this age. All of these men were persecuted for their beliefs, but they still made the effort to compile and record the history of their people.

Title illustration from L’Histoire Générale des Eglises Evangeliques des Vallées de Piemont ou Vaudoises by Jean Léger (1669)

And a wise choice it seemed to be, for within their lifetime, the Waldensians were severely oppressed and eventually evicted from their homeland in the Piedmontese Alps. Much of the earlier Waldensian volumes were lost, with the stark exception of what these men wrote.

Modern secular historians have devalued their accounts as propaganda meant to garner support from Protestant England against their Catholic tyrant, the Duke of Savoy. These scholars especially discount their assumptions that the Waldensian beliefs and practice had existed since the time of the apostles. And though not Waldensian himself, Samuel Morland’s The History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piemont became very influential in England; he often cited Perrin, Léger, Gilles, and other civic and religious documents.

Roman Catholics

The Roman Catholic Church was the preeminent power in Europe up until the Protestant Reformation, and it is that church that instigated the persecutions against the Waldensians. As homogeneous as the Catholic Church might seem, their writings about the Waldensians vary greatly.

Older sources included papal bulls (e.g. Ad abolendam by Lucius III and Ad extirpanda by Innocent IV), civil and inquisition court documents, and Church apologetics (Reinerus Sacho, “the anonymous inquisitor”, etc.). When Waldensians were mentioned in those documents even some inquisitors said they were “of great antiquity.” And that was in the 12th century. That doesn’t prove anything, but it is noteworthy.

Beginning in the 19th century and continuing to today, Catholic historians have taken a turn. Instead of medieval Waldensians being heretics, they have become little different from Francis of Assisi and his followers. According to them, Waldensians still observed the seven sacraments, their preachers (barbes) were observant Catholics, and there were no Waldensian churches (that’s a quick summarization, but the details vary depending on the scholar). I would place New Advent/The Catholic Encyclopedia in this category, as well as Gabriel Audisio (The Waldensian Dissent: Persecution and Survival, c.1170–c.1570), though he probably fits into the “Modern scholarship” category below too. I may disagree with many of the premises from these authors, but I have found their work to be well researched and insightful.

19th century Anglo Protestants and Baptists

Religious writing and history exploded in the 1800’s, most of it coming from England, Scotland, and the United States. Books about the Waldensians expanded greatly in popularity. This is also where one can start to observe the chains of citation that can occur in historiography. Early 19th century writers like Pierre Allix (Some Remarks Upon the Ecclesiastical History of the Ancient Churches of Piedmont) and William Jones (The History of the Christian Church from the Birth of Christ to the Xviii. Century) reached back in time to the aforementioned Perrin, Léger, Gilles, and Morland, while also consulting contemporary Waldensian pastors in Piedmont. From there, men ranging from theologians to doctors to poets traveled to the Piedmontese valleys, interviewed its inhabitants, and recorded their findings. Among others, these include Alexis Muston’s Israel of the Alps and James Wylie’s A History of Protestantism.

Books in this category tend to follow a similar pattern. I found them to be excellent sources for finding other sources that were closer to being primary or secondary. They were also rich in descriptions of the Alpine valleys, their culture, and their people. Their weakness, however, is how they romanticized the Waldensians, almost to a fault. Note that this was also the era of Romanticism in art and intellect; the accounts are breathtaking—even inspiring—but while researching, I had to make sure I didn’t hold a utopian imagination about who the medieval Waldensians were.

Modern scholarship

Earlier I mentioned Gabriel Audisio; he definitely falls into this category which took root in the mid-19th century and flourished through the 20th century. This is the mainstream view—the one most cited on Wikipedia, in academia, and in mainline Protestantism. These academics were often educated in the rationalistic German-speaking universities in Europe and applied their modernist presuppositions to church history, similar to how their contemporary peers reimagined biblical inerrancy, biblical criticism, and the origins of man. Instead of the Bible being an infallible source of truth, it became another dusty volume to validate. Most continental European Protestant theologians and pastors, whether Lutheran or Reformed, were influenced by this school of thought. And Waldensians, having joined the Reformation in the 16th century, were not excluded.

I have many disagreements with rationalist and humanist worldviews, but they were still sources that provided me with pages of notes. But before I read them (and after), I had to note who they were and the perspective from which they were writing. I found Gabriel Audisio to be mostly accurate, but in some areas (Waldensian progeny and practice), he was in deep disagreement with English church historians, medieval Catholic inquisitors, and the earlier Waldensians. He was a revisionist compared to earlier sources, mainly by applying 19th century rationalism to church history.

New Waldensians

Waldensians still exist today, both as a denomination and a people. Their main centers of learning are in Torre Pellice (La Torre in my books) and Rome. In their ancestral homeland of Italy, they have joined with the Methodists and are members of the World Council of Churches. Except for the Italian language they speak, they are quite similar to United Methodists, the United Church of Christ, and the Presbyterian Church USA; these are the same denominations that separated from their more conservative co-religionists in the early 20th century, and whose pulpits and centers of learning have become bastions of both political and theological liberalism. So, though I separate this into its own category, it has much in common with the rationalist scholarship group.

Emilio Comba was the vanguard of this movement, publishing his works about the Waldensians in the late 19th century. After the rationalist German scholars developed their hypotheses about early church history—including Waldensians—Comba followed their example but went deeper, going as far as to label the earlier Waldensian writers (Perrin, Léger, Gilles) as fabricators and not true Waldensians.

Emilio Comba

I found Comba to be one of the most difficult scholars to read; his knowledge is obviously vast, but the way he bemoans nearly everyone before him who wrote about Waldensians comes across as elitist, which is congruent with continental scholarship in that era (higher criticism, rationalism, Darwinism, etc.).

One hundred years later, Giorgio Tourn, another Waldensian pastor, wrote You Are My Witnesses: The Waldensians Across Eight Hundred Years (1989). Tourn takes a much more moderate stance than Comba, and I personally found him to be a great resource.

Church history enthusiasts

This category covers a lot, but I still separate it from the others. These books tend to come from those who either teach church history or who have a general interest in the subject, but aren’t theologically liberal. They cite the other sources mentioned in this article (especially the “Old Waldensians” and “19th century Anglo Protestants and Baptists”), and they can give new readers interested in the Waldensians a high-level overview.

I spent the least amount of time in these books, but they still have value, especially for the casual reader.

Back to historical fiction

I’ll self-label my own historical fiction works as having facts from a variety of sources (by my count, 60 books), but where there is variance between those sources, my suppositions usually follow the aforementioned “Old Waldensians” and “19th century Anglo Protestants and Baptists” sources. That’s not to say I didn’t glean facts from the other categories (Audisio’s Preachers by Night was very informative), yet the themes, the historicity, the recollections, and the imagery of Heretics of Piedmont and The Lord of Luserna were most influenced by traditional historians.